Night Vision

Community unfolds the remarkable life of the Underground Railroad’s fearless conductor, Harriet Tubman, who suffered during much of her life from a chronic, debilitating disorder.

Araminta Ross, who later become known as Harriet Tubman, “the Conductor of the Underground Railroad,” “General Tubman,” and “Moses,” was born to Benjamin Ross and Harriet Green, one of nine children, sometime between 1820 and 1824 in Dorchester County, Maryland, on the plantation of Anthony Thompson.

Araminta Ross, who later become known as Harriet Tubman, “the Conductor of the Underground Railroad,” “General Tubman,” and “Moses,” was born to Benjamin Ross and Harriet Green, one of nine children, sometime between 1820 and 1824 in Dorchester County, Maryland, on the plantation of Anthony Thompson.

Tubman’s birth year is uncertain, however a record of a payment to a midwife indicates that it was probably 1822. As an adult, she took her mother’s name, “Harriet,” and the surname, “Tubman,” when she married John Tubman.

Tubman’s father was enslaved by Thompson, while she, her mother, and her siblings were enslaved by Thompson’s stepson, the farmer Edward Brodess. As a very young child, Araminta, who was known as “Minty,” was put to work. Brodess hired her out to other landowners, who treated her cruelly, brutally whipping her, and leaving deep scars. Even when sick with measles, Tubman was forced to haul muskrat traps through frozen swamps, wearing no shoes, her feet only covered with cloth.

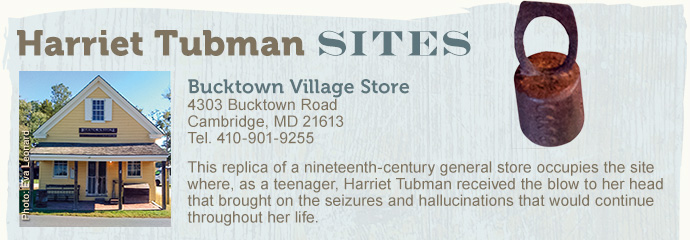

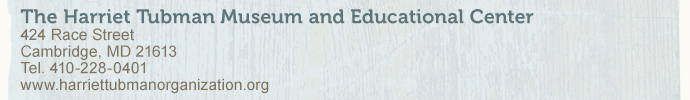

(Above) Freedmen laborers at Quartermaster’s Wharf, Alexandria, Virginia. African-American dockworkers and mariners taught Harriet Tubman to follow the North Star to freedom. Photo: Mathew Brady, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (Below, right) A two-pound counterweight of the type that fractured Tubman’s skull, causing her life-long disability. Photo: Eva Leonard

As a teenager, following a severe head injury—the result of her efforts to protect another slave—Tubman developed a lifelong, chronic condition, with debilitating symptoms that have been described as being similar to those of narcolepsy and temporal lobe epilepsy.

At the local general store, she had encountered an unidentified young male slave, there without permission. An overseer ordered Tubman to restrain the young man, and hurled a two-pound counterweight at him. Instead, after he darted out of the store, Tubman blocked the doorway. The weight hit Tubman in the head, fracturing her skull and nearly killing her.

Recovering from the blow without medical care, she was forced back to work only two days later, as her head bled from the injury. After the injury, Tubman began to experience uncontrollable episodes, which could happen several times a day, as she fell into a motionless, dream-like state, lasting from half an hour to an hour, during which she hallucinated.

Recovering from the blow without medical care, she was forced back to work only two days later, as her head bled from the injury. After the injury, Tubman began to experience uncontrollable episodes, which could happen several times a day, as she fell into a motionless, dream-like state, lasting from half an hour to an hour, during which she hallucinated.

The attacks occurred without warning, even in the middle of conversation. When an attack ended, she resumed the conversation where it had stopped. Tubman described the hallucinations as “visions,” in which she sometimes saw herself flying above the earth and over water.

Kate Larson, author of “Harriet Tubman, Portrait of An American Hero: Bound for the Promised Land,” says that during these states, Tubman also heard the sounds of voices, screams, music, and rushing water, and felt as though her skin was on fire, while still conscious and aware of what was going on around her. She also experienced extreme, debilitating headaches, and became increasingly religious after the injury.

Initially, Tubman’s injuries made it difficult for her to work and lowered her value as a slave, and she was returned to Brodess. But she grew stronger as she recovered and worked digging out stumps, plowing fields, chopping wood, and hauling timber.

In 1844, at the age of 25, she married John Tubman, a free black man. When Edward Brodess died in March of 1849, he left his wife, Eliza, deeply in debt. Fearful that Eliza Brodess would further split up her family by selling them South to work on chain gangs to pay the debt, Tubman escaped to Philadelphia later that year. (She had watched her two older sisters, Linah and Soph, sold out of state as part of a chain gang when she was younger.)

She traveled the approximately 90 miles to Philadelphia on foot, at night, following the North Star, which she had learned of from the African-American dockworkers and mariners she befriended as she loaded and unloaded produce at the wharves. The mariners served as a vital link in the Underground Railroad’s communication network, delivering coded messages and providing information about the outside world for those seeking freedom.

On her way to Philadelphia, Tubman stopped at Underground Railroad safe houses, where she was fed, sheltered and directed to the next house by Quakers and black and white abolitionists.

Tubman described her emotions on finally crossing the border into the free state of Pennsylvania: “I had crossed the line of which I had so long been dreaming. I was free, but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land, and my home after all was down in the old cabin quarter, with the old folks, and my brothers and sisters. But to this solemn resolution I came; I was free, and they should be free also; I would make a home for them in the North and the Lord helping me, I would bring them all there.”

In Philadelphia, and in Cape May, New Jersey, Tubman found work as a domestic, and as a cook in hotels, earning money to return to Maryland and bring her family to freedom.

In 1850, Tubman made her first trip back to Maryland to retrieve her niece and her niece’s son and daughter. In 1851, she came back for her husband, John Tubman, but discovered that he had remarried and did not want to join her. Instead, she found a group of slaves eager to leave, and brought them to Pennsylvania with her.

During an estimated 13 trips, over the course of a decade, Tubman brought at least 70 slaves, including many family members, to freedom, never losing a passenger. Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, it was no longer safe to end the journey in the northern states, so Tubman began to bring her passengers to Saint Catharines, Ontario, Canada, where she moved in 1851.

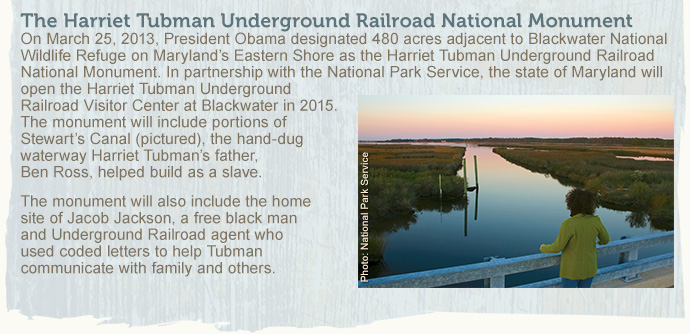

In 1854, Tubman sent a coded letter through a friend to Jacob Jackson, a free, literate black man who lived near Tubman’s family in Maryland. The letter alerted Tubman’s three brothers to her plans to return and bring them back with her to Philadelphia. In 1857, she also brought her elderly parents to freedom.

Tubman led her escapes at night, following the North Star, using a variety of strategies to evade detection and capture. On one trip she disguised herself as a man, and on another, she carried chickens to make it look as though she were running errands. She sometimes wore a silk dress to appear a free, middle-class woman, and she often led Saturday night departures because “Wanted” posters could not be printed until Monday mornings, giving her a one-day head start.

Tubman carried the drug paregoric to prevent babies from crying during the trip. She also packed a pistol as protection against slave catchers, and as a warning for passengers who might be tempted to abandon the escape and turn back. Tubman was fearful that if they did turn back, they would divulge what they knew about the Underground Railroad.

In a December 29, 1854 letter, Thomas Garret, Wilmington, Delaware Underground Railroad Stationmaster wrote to J. Miller McKim: “We made arrangements last night, and sent away Harriet Tubman, with six men and one woman to Allen Agnew’s, to be forwarded across the country to the city. Harriet, and one of the men had worn the shoes off their feet, and I gave them two dollars to help fit them out, and directed a carriage to be hired at my expense, to take them out….”

In 1859, Tubman moved to Auburn, New York, purchasing a house from her friend, Senator William H. Seward, and bringing her parents with her. She would also open her home to other relatives, as well as friends and former slaves.

In 1859, Tubman moved to Auburn, New York, purchasing a house from her friend, Senator William H. Seward, and bringing her parents with her. She would also open her home to other relatives, as well as friends and former slaves.

After the Civil War began in 1861, Tubman worked with the Union Army in South Carolina, Virginia, and Florida as a scout, spy, leader, and nurse. Known for her abilities as a healer and a caregiver, Tubman brought ill soldiers back to health, using herbal treatments she knew from growing up in the Maryland countryside, and drugs she had learned about from Edward Brodess’s stepbrother, a doctor who ran a pharmacy. To heal soldiers who were sick, and in some cases, dying, from dysentery, she treated them with a tea she brewed using herbs and roots with medicinal properties.

Disguising herself as a sick, elderly woman, she performed reconnaissance for the Union army in Confederate towns. In 1863 Tubman scouted and planned for the Raid at Combahee Ferry, commanded by Colonel James Montgomery, and led 300 black soldiers during the raid, which freed more than 700 slaves in South Carolina. Tubman also recruited volunteers for John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, but was unable to join the raid.

In 1869, Tubman married Union Army veteran Nelson Davis, whom she had met in Auburn. Despite her own accomplishments, Tubman was for many years denied her own military pension, although she received one as Davis’ widow after he died. She finally was granted one for her own service in 1899.

Sometime during the late 1890s, Tubman had brain surgery at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital to relieve the pain she had dealt with much of her life from her childhood injury. Although details are scarce, the operation gave her some relief from the symptoms caused by the blow she had received some 60 years earlier.

In 1908, Tubman founded the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged in Auburn, New York. Her friend and neighbor Helen Tatlock said that at her home, Tubman took care of “the demented, the epileptic, the blind, the paralyzed, [and] the consumptive.” When Tubman herself grew frail, she would be cared for in the home she had established.

When Harriet Tubman died of pneumonia in 1913 in Auburn, New York, she was buried with full military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery. Nearly fifty years earlier, the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, had written in a letter to Tubman: “The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day—you in the night. … The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism.”

Contact us

Did you enjoy this story? Email us your comments and questions and let's keep the conversation going. We encourage you to engage with us and other readers by following us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest. Every person's journey is unique, and every perspective is valuable to us.