Tag Archives: Lung Transplant

High Notes

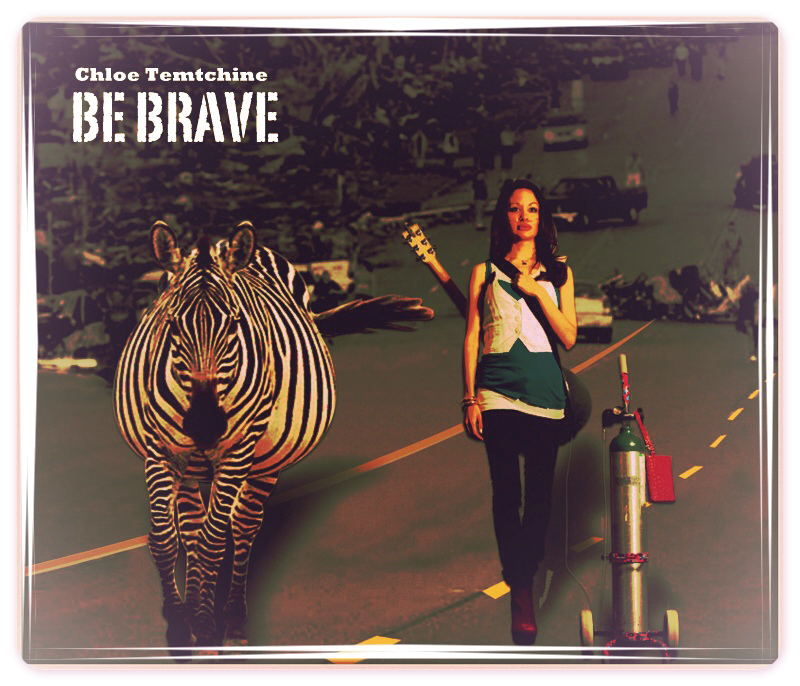

March 24, 2014New York-based singer, songwriter and musician Chloe Temtchine has won rave reviews and awards for her solo work and collaborations with other top music industry artists. On March 29, 2014, Temtchine’s new song, “Be Brave,” will be released on iTunes, with fifty percent of the proceeds benefiting PHA. Diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension in 2013, Temtchine performs with her oxygen tank, which she has dubbed “Steve Martin,” alongside her. Community spoke with Temtchine about life, music and pulmonary hypertension.

When did you start singing and songwriting? Who and which styles are some of your biggest influences?

When did you start singing and songwriting? Who and which styles are some of your biggest influences?

I started singing at about the age of six. My father used to take me to a Baptist church in Harlem, on Sundays, where I listened to gospel music for hours. That’s where it all began.

I’ve always had very eclectic taste in music: from artists like Edy Phenomene (French dancehall), to Smokie Norful and Kim Burrell (gospel), to Stevie Wonder and Sam Cooke (R&B/soul), to James Vincent McMorrow and Ray Lamontagne (singers/songwriters), to Eric Reed (jazz). The list could go on forever.

When and how were you first diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension? What were your initial symptoms?

In March 2013, after my cardiologist reviewed an echo and listened to my heart, I was diagnosed with severe pulmonary hypertension and was rushed to the ER. The shortness of breath, lung pain, and fatigue that had started five years previously had become progressively worse, and I had reached a point where I could barely move. Getting to the bathroom was a major accomplishment! Then my heart started beating out of my chest. And then, together with the continued chest pain that accompanied every breath, I suddenly put on 10 pounds of water weight overnight.

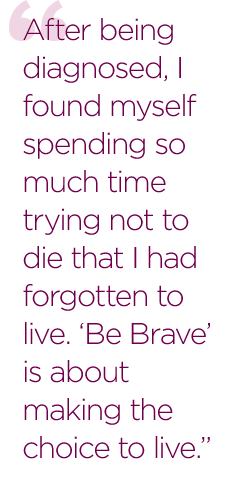

What is “Be Brave” about?

After being diagnosed, I found myself spending so much time trying not to die that I had forgotten to live. “Be Brave” is about making the choice to live.

Every time I went to the hospital, I came home feeling that there was very little hope. I realized that if I didn’t shift my consciousness quickly, my condition would continue to get worse.

I’m a big believer that our minds play a huge role in the state of our health. Keeping my mind in the right place is so important to me that I decided to write a song about it. I wanted to remind myself, and anyone else going through a similar experience, that any challenge had the potential to be an opportunity.

What inspires you in songwriting?

I’m much more comfortable expressing myself through song. Music captures the way I feel in a way that words without melody can’t seem to do.

What have you learned in dealing with pulmonary hypertension? What have been some of your biggest challenges, and how have you dealt with them?

What have you learned in dealing with pulmonary hypertension? What have been some of your biggest challenges, and how have you dealt with them?

Although I would do just about anything not to have pulmonary hypertension, I’ve understood through this process that there are many lessons I’m meant to be learning. I am very grateful for the perspective it has given me with regard to my life.

My biggest challenge was seeing a future when I was told that it was highly unlikely that I would have one. This continues to be my biggest challenge.

What do you think is most important for the newly diagnosed to know about pulmonary hypertension?

For the newly diagnosed, I would say: Surround yourself with positive people who instill hope in you, eat a very healthy diet (plant-based, if possible), go to pulmonary therapy, focus on other people’s success stories, and most importantly, believe that it is possible to get better no matter what you’ve been told.

How does being a singer, musician and songwriter help you deal with pulmonary hypertension?

I think that being inspired and passionate in general is helpful to anyone. I also think that it’s very important to express yourself in order to keep yourself in balance. Through music, I’m able to get out all of the things that I would otherwise potentially keep in.

What is next for you in terms of treatment for PH?

I’m not totally sure at the moment. Because there is a belief that I may have pulmonary veno-occlusive disease in addition to PH, my doctor is going very slowly with the medications, which I’m very grateful for. Lung transplantation has been suggested, and although I’m thankful that it exists as an option, my goal is to stay away from it, if at all possible.

What’s next for you in music?

My next goal in music is to finish writing the album I began when I got out of the critical care unit and to perform as much as possible.

What do you enjoy most about music?

I love that music has always had the ability to completely alter the way I feel. It has helped me be hopeful during very difficult times. I love the idea of creating something that could not only alter my own state, but that also has the potential to alter the state of someone else who may be in need of some state-altering!

—EL

Posted in About Us, Diseases, Featured, Uncategorized | Tagged be brave, chloe temtchine, Lung Transplant, music, PH, PHA, Pulmonary Hypertension, Pulmonary Hypertension Association, Pulmonary Veno-Occlusive Disease, singing, veno occlusive | 3 CommentsNewsmaker Q&A with Thomas L. Spray, M.D.

November 1, 2013 Thomas L. Spray, M.D., is chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, director of the hospital’s Thoracic Organ Transplantation Program, and Professor of Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Community recently interviewed Dr. Spray about pediatric lung transplantation.

Thomas L. Spray, M.D., is chief of the Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, director of the hospital’s Thoracic Organ Transplantation Program, and Professor of Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Community recently interviewed Dr. Spray about pediatric lung transplantation.

What are the most important considerations for parents when making decisions about pediatric lung transplants?

The fundamental issue here is that, lung transplantation is, unlike heart transplantation, not associated with as good long-term survival. In some ways it’s somewhat palliative. Five-year survival for lung transplant is about 50 percent. And despite lung transplants being around now for about 25 years, there hasn’t been a lot of improvement in survival.

The lung is an immunocompetent organ, unlike most other organ transplants. It has the disadvantages of being connected to the outside, so it’s always at risk of infection. Also, there are lymph nodes in the lungs, which probably make them more susceptible to rejection and latent chronic rejection, which is where most lung transplants eventually fail; something called bronchiolitis obliterans—scarring of the small airways of the lungs—which is thought to largely be a chronic rejection problem.

Having said that, there are isolated patients who do extremely well and do well over the long term, but if you just take the averages, the average survival is about five years. So that’s the disadvantage.

On the other hand, for many patients, especially pediatric patients, their survival is going to be measured in a matter of a year or less if they don’t get a lung transplant. So it’s successful, but it’s not perfect by any means. It’s generally very much palliative for children as well.

To what degree should the child be involved in the decision?

To what degree the child should be involved in the decision is somewhat age-dependent. When you have a lung transplant, you’re basically exchanging one disease for another one, because you then have to be on medicines to prevent rejection, and you have a certain amount of medical surveillance necessary.

Unfortunately lung transplantation is still a procedure that has a significant risk associated with it. The lungs cannot work sometimes. The outcome cannot be positive if you get a viral infection of the transplant early on—it can destroy the lungs. And that’s very hard for anyone to survive.

I can remember some patients though, with cystic fibrosis, after lung transplant, even when the lungs went bad, and they ultimately died, having said during the time they were alive, that it was worth everything just to breathe normally for a change. So you have to put it in perspective.

When you get into the teenage years, I think it’s appropriate for the child to be involved in the decision. I think it’s especially important for teenagers, who unfortunately have a fairly high risk of not being compliant with medical management, and then they reject their organs and die.

Just being an adolescent is a risk factor for transplant, it appears. It’s a difficult time. That’s why when you’re talking teenagers, it’s very important that they be involved in the decision process, so that they recognize that they have to be involved in the medical management. They have to take their medicines faithfully. They have to be seen frequently. And if they aren’t willing to do that, then it’s kind of foolish to go down that pathway.

What have been some of the advances in pediatric lung transplantation?

Patient room at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Most of the advances in transplantation, in terms of survival, over the last 15 years, have been at the early period after transplant. In other words, we’ve been able to transplant more complex patients, who’ve had multiple previous operations, who were sicker waiting for transplant.

We’ve evolved to the point where it’s now possible to support patients on an assist device called ECMO while waiting for transplant and still have them able to be up and around and maintain their ability to breathe, so that it makes it easier after the transplant. So there are some advances, but there haven’t been any major advances in immunosuppression.

We have experience now transplanting newborns all the way up to adults. We’ve had experience with many kinds of complex congenital heart disease and lung transplants. We have experience in pulmonary hypertension. Those are the more common causes in children.

I think it’s important to note that in the pediatric world, the most common indications for transplant are considered the higher risk indications in the adult world. For example, in adult lung transplant, the most common indication is emphysema. Emphysema is a more straightforward condition to treat with lung transplant than any of the diseases that we see in children, and emphysema is virtually unheard of in children, so pediatric transplant by its very nature is a higher risk population.

What percentage of pediatric transplant patients have pulmonary hypertension?

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, at least 50 percent or more have congenital heart disease or pulmonary hypertension, and relatively fewer have cystic fibrosis. Part of that is because the management of cystic fibrosis has improved over the years such that there are relativity fewer children who require transplantation for cystic fibrosis than in the past. So, most people with cystic fibrosis can get to adulthood before they have enough lung deterioration to require transplant, and therefore get transplanted in adult centers now.

When we first started doing lung transplant in about 1990, when I was in St. Louis, cystic fibrosis was a common indication, because children under 18 with severe cystic fibrosis would come to St. Louis for transplant. In Philadelphia, we see less of that and more pulmonary hypertension and congenital heart disease.

What drew you to the lung transplantation field?

I started out as a congenital heart surgeon. Congenital heart surgeons all have to be adult heart surgeons first. I did adult and congenital heart surgery at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. I was recruited to come here to take over from William Norwood, a very well known surgeon, who went to Europe to start a new program.

When I came to Philadelphia, there wasn’t a lung transplant program in this area. So I started a pediatric lung transplant program when I came in 1994, having started the program in St. Louis in 1990.

I think my interest in lung transplant came from patients I saw in St. Louis who had no real, good option for repair of their heart, because they didn’t have good lungs to push blood into. There are certain types of congenital heart disease where that’s the case, where you could repair the heart defect if you had pulmonary arteries to pump blood into.

But children who don’t have that became progressively more cyanotic. I saw some of these children and I thought, ‘If we could just put new lungs in, we could fix the heart.’ So that’s what got me interested initially, and then that expanded to all the other potential reasons for lung transplant, of which there are many.

What are some of the differences in quality of life after a successful pediatric lung transplant?

Art therapy at The Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia

Quality of life depends on the patient’s condition before the transplant, but the majority in the pediatric population are extremely debilitated. They often have cystic fibrosis. They’re chronically infected. They have poor lung function. They have very little exercise tolerance. Patients with PH may have heart failure also. So the quality of life prior to transplant is very poor.

The waiting times are so long for lung transplant that most children deteriorate significantly while waiting in the hospital. They’re sometimes waiting in the hospital for a year or more.

So the quality of life after transplant, while vastly improved, takes a while for them to recuperate. I think what people often don’t realize is that if you’re sick for months and months prior to lung transplantation, there’s a lot of rehabilitation necessary. Even after a successful lung transplant, it’s not like patients are going home in a week. Many of them have to stay in the hospital for months while they’re literally recuperating and rehabilitating themselves from being chronically ill for the previous several years.

How much interaction do your patients have with the Child Life, Education and Creative Arts Therapy department at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia?

They have a great deal of interaction, especially while waiting. Children who are sick and in the hospital and literally waiting for sometimes months and months for organs to become available need that kind of interaction. They need to have play.

They need to have creative interactions, and that’s why the Child Life Department is so important for all the patients in the hospital, but even more important for those who are chronically in the hospital for long periods of time. They need to have that kind of stimulation. They need to be able to be involved in arts and crafts to keep them occupied, literally, to help them develop while they’re waiting.

What are some ways that families can cope with being on a waiting list?

Everyone, I think, does that differently. I think it’s always difficult for families to recognize that a waiting list is exactly that. You have no idea when organs might become available.

There are times when organs are available, and we tentatively accept them, and then they deteriorate to the point that we can’t use them. So the families have situations where their hopes are raised that they’ll have a transplant, and then it falls through, and then they’re back waiting again. So it’s a difficult thing for the families.

I think the families need to recognize that donor organs are hard to come by; they’re very scarce. The organ system is as fair and open as people can make it. It’s constantly trying to be as completely open and straightforward as possible and to not disadvantage anybody and make everybody on an equal playing field. But these are difficult things sometimes.

Transplantation in some ways is kind of a fundamentally flawed strategy, because you have to have a tragedy to have a miracle. Someone has to die for organs to be available, and as a physician and surgeon, I don’t want anyone to die. In a way, I don’t want there to be more donors.

On the other hand, I think the donors who are available should be used as maximally as possible, because there are so many children who need the organs. It’s a constant battle to try to use everyorgan you possibly can. But then some of them have problems and don’t work. That’s unfortunately the chance you take.

What programs are in place at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to help families afford the cost of pediatric lung transplants?

Art Therapy at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

There’s a whole process before someone is listed for transplantation that involves evaluating their financial situation. The hospital has many programs to try to get them into programs that will provide coverage. Because it makes little sense to do a lung transplant if you have no coverage for medications after the transplant, which happens in some crazy insurance arrangements.

The hospital sometimes will help families get Medicaid or some other government program that will at least provide them with follow-up medications and follow-up care. There’s a whole financial counseling group that works with families in relation to transplant, because you have to recognize it’s not a one-time deal. It’s like a new disease, if you will, transplantation.

What else is important to stress about how pediatric lung transplants are different from adult transplants?

The diseases are different, and they’re more complex. Many of the [pediatric] patients have had previous surgeries, which complicate the transplant significantly, in terms of bleeding and other issues.

I’ve said many times that the hardest part of transplantation is not putting the new organs in; it’s getting the old ones out. That can be extremely difficult due to the scarring and inflammation and previous infections. It can sometimes be extremely difficult just to get the old organs out without damaging other important structures. They can all be stuck together in the chest.

That’s one major challenge with lung transplant, especially in children. It’s not as common in adults. Most of the adults with emphysema have not had significant previous surgeries; they don’t have a lot of extra blood vessels.

Many of the children who need transplant are also ‘blue.’ They’re cyanotic. They don’t have normal oxygen levels. That stimulates development of blood vessels in the chest that can be very difficult to control at the time of transplant, and bleeding is much more of an issue.

Then of course we’re dealing with different sizes. In adults, they’re using mostly adult lungs and some teenage lungs. But in pediatric transplantation, we have to list patients in a very discrete size range, because we do transplants in patients all the way from newborns up to adult-size teenagers. So we have to have the ability to put very small lungs in small children.

We do occasionally use lobes or parts of lungs from adults in small children, which is something the adult world rarely, if ever does, because we have to deal with this wide size range.

All photos courtesy of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Posted in Diseases, Featured, Uncategorized | Tagged bronchiolitis obliterans, child transplantation, Children's Hospital, congenital heart disease, creative arts, cystic fibrosis, ECMO, health, immunocompetent organ, immunosuppression, Lung Transplant, medical, medicine, organ donor, pediatric, Philadelphia, Pulmonary Hypertension, surgery, therapy, Thomas L Spray MD, Thomas Spray, Thoracic organ transplant, university of pensylvania | Leave a commentEsen’s Story

August 2, 2012My journey began in September 1998 when I was diagnosed with PPH (Primary Pulmonary Hypertension). When I was first informed about my illness, I was relived because I had always known there was something wrong with me.

I was told in such a cruel way though. I had just started working in a law firm as a secretary and it was only my third day, but I had a hospital appointment in the afternoon so I took the afternoon off. I wasn’t going to go but something that day made me! I met my mum outside the hospital and we went in. The doctor asked me about my symptoms, which included fainting, blue lips, palpitations, and always finding it hard to catch my breath. He said he wanted an ECHO so I went into the next room and had to take off my top and bra. I felt scared because they didn’t let my mum in to be with me. The nurse put a cold jelly on my chest and did the examination.

We waited another hour before the doctor told us that I would need a transplant. I was given the name of the illness but no explanation as to what it was or anything, just that it was very rare. Then I was taken into another room where there were loads of student doctors, as the doctor thought they should listen to my heart and lungs to learn. I was in shock, I felt sick, and now I was being prodded like a guinea pig. Finally, I just burst into tears, but they kept on listening. It was one of the hardest days of my life.

I was admitted and then sent onto Papworth Hospital in Cambridge, England, where I got the best care. I came to understand my illness and realize it was now a part of me and we had to live together.

But I knew I would beat it.

I was put on the transplant list in June 2002 (during the World Cup!). My PH doctor, Joanna, was the first to mention the transplant waiting list to my family and me when I was about 22 years old. The doctors estimated that I would have to wait for 1 to 2 years, and maybe even more. I didn’t want to be negative about it. Instead, I wanted to keep a positive outlook on things, so I really didn’t listen to the doctor when he was saying all the bad stuff. I thought, “No, I’m going to get better!” And in nine months my time came! I had a heart and double lung transplant on March 18, 2003.

I spent a week with my transplant team early on in the process. I had tests; from blood tests to echoes to x-rays. They explained to me everything that I should expect about having such a big operation, including taking medication and all the possible side effects. What I remember most was one of the nurses saying to me that I would get facial hair and asking if I would be okay with that. My reply to her was that that would be a simple problem compared to the ones I have now. I also saw a psychologist to help me with my fears about the transplant and everything else I was worried about.

My family was my rock during this difficult time, especially my mum! She was, and still is my rock! My friends kept their distances. I think they were scared that they were going to lose me so they chose to bury their heads in the sand. The only support I got from the hospital was from the PH team and from a Macmillan nurse by the name of Sarah. I remember telling her that “this PH will never beat me, I will fight it until the end and beat it!” My mum always said to me, “if God gave this illness to you, he also [will give] you a cure!”

What gave me hope in the midst of my journey with PPH was meeting my husband to be in 1999! He gave me hope when I thought no one would want an ill person or someone who might die soon. But he loved me unconditionally and didn’t listen to those who were telling him to forget me. He fought for me and I fought my illness.

It was St. Patrick’s’ Day, March 17th, when I got the call. I was in my room, as I was bedridden, and watching my favorite soap, “Eastenders” and I remember my grandmother coming to my room with the phone and saying that a nice man was on the line. I didn’t think anything of it because I thought my fiancé was calling. I realized it wasn’t him, but instead my transplant coordinator, Steven. He asked if I would like to get my new heart and lungs, and I thought he was joking and said, “But I’m busy watching TV!” (I guess it was the shock.) I had an hour to get ready, so my mum took me to the bath to bathe me and I remember all of my family being there and how hard it was saying goodbye because it might have been the last time I was going to see them.

I was being brave, but my emotions were all over the place. I was happy, scared, sad, sick and tearful. I felt sad that someone out there was dying to save me but I tried not to think about this too much because it was very hard to deal with on top of everything that was happening. After my transplant, I wrote the family a letter to tell them that I was doing well and how their loved one saved me and gave me back a normal life. To me, they will always be my angels who were put on this earth to save me, and who I’m grateful for each extra day I have with my loved ones.

My life has changed forever! The transplant gave me back my life. It was like I was reborn. Before the transplant I was in a wheelchair, and on 24-hour oxygen and I needed help with dressing or bathing. I came home from the hospital a month after my transplant, and it took me quite a while to adjust to doing things for myself again. I was apprehensive of everything. I was scared that I would get ill again. I felt alive, yet guilty of it. I didn’t feel the need for oxygen but still wanted to use my wheelchair but my mum put it away! I was doing exercises the physiotherapist gave me which helped me to gain my strength back.

Today, 9 years after the transplant, my life is a happy one. I’ve been happily married since 2004. I don’t want to paint a picture of a perfect life after a transplant because it’s hard with all the medications’ side effects. They consisted of putting on weight and getting excess hair on your face and body. You get an appetite so be careful! I put on so much weight and had to lose it all! Two other side effects include very bad shakes and a puffy face from the steroids. I could always tell when someone is on steroids because my own face was the same! It may not be perfect, but when I think back to how I was before, I wouldn’t change anything.

It took me over a year to fully recover from the transplant. The first year I got CMV (Cytomegalovirus) and I was scared I made a big mistake in having the transplant. But once I recovered from that, everything got better and I got used to the medication (much simpler than the ones from PH) that I had took just twice a day!

The advice I would give to people who have been diagnosed with PPH would be: Be strong. Be brave. Laugh at yourself! Make fun of the PH, that’s what my mum and me did. And still do! There were days that I just wanted to give up to die and be done with it, but that feeling never lasted long! I think I’m the sort of person who cannot stay depressed for too long. I find happiness in the smallest things. Like I love opening a new jar of Nutella the most! Also, I think my family and husband help make me who I am. They give me the strength and love I need. My faith helps me too. Praying and believing in your dreams is vital to helping a person get through obstacles. To me, it doesn’t matter what religion you believe in, just that the power of belief is stronger than anything is possible. I think (and it might sound wrong to others) that everything happens for a reason and that you must always look for the good in that reason, in order to go on with life.

On the night of March 17, 2003, an angel saved me. I’m forever grateful to you. You gave me back a life I never thought I would see. I live each day a happy one with the people I love.

Posted in Diseases, Featured, Media Center | Tagged Heart Transplant, Lung Transplant, PPH, Pulmonary Hypertension, Share Your Story | 6 Comments